The European Space Agency has announced a multi-billion-Euro investment to the robotic and human exploration of the Solar System. It represents a large expansion to the contribution that Europe is already making to Artemis, the NASA programme to land the first woman and the next man on the Moon during 2024.

The new contracts are worth a total of €2.9 billion and are designed to help Artemis become a long-term sustainable exploration of the Moon by astronauts, and take Mars exploration to the next level by returning Martian rocks to Earth for analysis.

ESA’s involvement in these programmes has been made possible thanks to funding decisions taken in Seville, Spain, last year by the science ministers of ESA’s 22 Member States. At the end of two days of negotiations they endorsed the most ambitious plan to date for the future of ESA and the whole European space sector.

“The decisions taken in Seville were fundamental. They basically set us with a programme for this coming decade,” says David Parker, ESA’s director of Human and Robotic Exploration.

Read more about ESA:

- Race to Venus: What we'll discover on Earth's toxic twin

- How the Parker Solar Probe will 'touch the Sun'

- Comet interceptor: Unlocking the secrets of the early Solar System

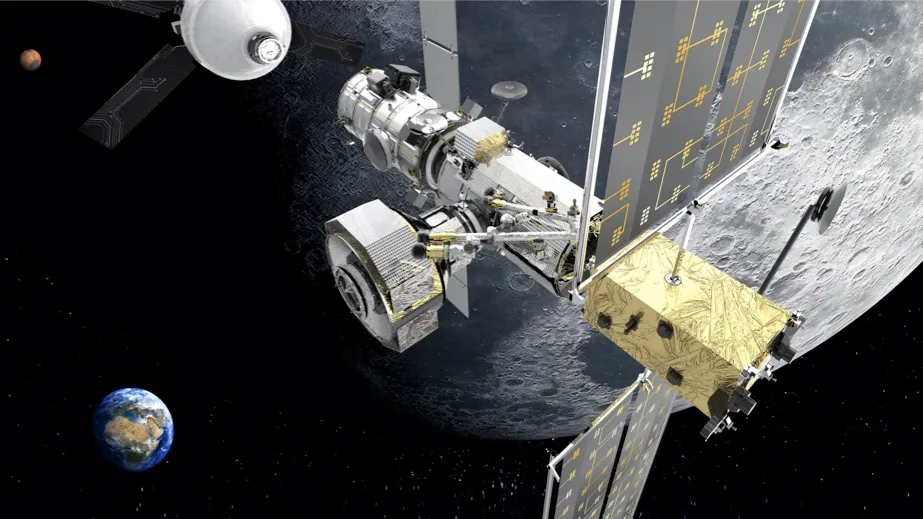

Europe is already involved in NASA’s Orion spacecraft, which will transport astronauts to the Moon and, potentially, other destinations in the Solar System. The European Service Module supplies the Orion crew capsule with air, water and electricity. It keeps the spacecraft on course and at the right temperature. ESA will be supplying at least four service modules, with the potential for another two after that. They will help deliver astronauts to the lunar gateway, a space station in orbit around the Moon.

ESA is committed to delivering two modules to the gateway. The first is the International Habitat (I-Hab). It will be a pressurised living area with docking ports for visiting vehicles, supplied by Thales Alenia Space, Italy, and launched in 2025.

The second is ESPRIT, European Systems Providing Refuelling Infrastructure and Telecommunications. It will function as a communications relay between astronauts on the surface of the Moon and Earth, and will take additional fuel to the gateway to keep it operational well into the 2030s. It will also feature a spectacular viewing port so that astronauts can gaze at the surface of the Moon. The communications part will launch in 2022, while the main refuelling module and viewing ports will launch in 2027. Even before then, NASA and ESA plan a lot of lunar activity.

In September NASA published its plan for the first phase of Artemis, which culminates in the human landing of 2024.

“We will return to the Moon robotically beginning next year, send astronauts to the surface within four years, and build a long-term presence on the Moon by the end of the decade,” says NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in the document.

The first mission, known as Artemis I, is on track for 2021. NASA’s new rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS), will take the Orion capsule around the far-side of the Moon for a test without astronauts. Artemis II will fly with astronauts in 2023, more or less repeating it predecessor’s journey.

During this time, NASA, ESA and other international partners will be landing robotic equipment on the lunar surface to conduct preparatory experiments. The Prospect instrument is a robotic drill and a miniature laboratory that will fly on the Russian Luna-27 mission, slated for launch in 2025. Built by Leonardo, Italy, it will study the composition of the soil near the lunar south pole, which contains water essential for sustainable human exploration.

Artemis III is the mission that will take humans to the surface the Moon. This is the part of the mission with the most question marks about whether it will be ready in time. NASA has awarded contracts to three different industrial consortia to study possible designs for this spacecraft. But it will be a close-run thing to have it ready, tested and working by 2024.

Whenever that mission lands humans on the Moon, ESA will support the activity by providing communications through the Lunar Pathfinder satellite. Built by Surrey Satellites Technology, UK, ESA will buy telecommunications services from them, effectively helping to fund the spacecraft.

ESA has also begun studying the European Large Logistics Lander (EL3) with the company Airbus, Germany. “We need a lunar transit van,” says Parker, “Something that can land a tonne and a half of payload to support human exploration.”

EL3 is just that. It is being designed to land anything from rovers to food and other supplies such as oxygen, science instruments and experimental equipment to extract lunar resources to make water and oxygen.

Up until now, it has been easy to think that NASA’s plans to return to the Moon have been a largely solitary endeavour tinged with political motives that could evaporate if the White House changes hands in November. Now, however, the international contributions show how robust the programme is. Europe is the strongest partner but others, such as Canada, Japan and Australia, are joining too.

Also, the language in NASA’s September announcement stresses the broad support for the programme in America’s government.

“With bipartisan support from Congress, our 21st Century push to the Moon is well within America’s reach,” says Bridenstine. “As we’ve solidified more of our exploration plans in recent months, we’ve continued to refine our budget and architecture. We’re going back to the Moon for scientific discovery, economic benefits, and inspiration for a new a generation of explorers. As we build up a sustainable presence, we’re also building momentum toward those first human steps on the Red Planet.”

Before those human steps can be taken on Mars, more robotic ones will have to be made. And so contracts have now been announced for future Mars missions in which ESA and NASA will collaborate to bring back samples of the Red Planet to Earth by 2031.

NASA’s Perseverance rover is currently en route to a February 2021 touch down. In its exploration of Mars, it will cache interesting looking rock samples in collection tubes. ESA has now committed to two missions to help bring those tubes back to Earth.

The Sample Fetch Rover will navigate autonomously, detect the tubes, pick them up and place them in a canister on a NASA supplied Mars Ascent Vehicle. The Sample Fetch Rover will be supplied by Airbus, UK. Once the NASA vehicle reaches Mars orbit, it will release the sample canister, which will be captured by ESA’s Earth Return Vehicle, which will bring them to Earth. This spacecraft will be supplied by Airbus, France.

As well as collecting invaluable geological samples, such a mission is also a prelude to human exploration. “Sample return is scientifically worth doing on its own merits, because bringing back pristine Mars material will transform our understanding of the Red Planet,” says Parker, “But it's also kind of a scale model of an eventual human Mars mission.” This is because the sample return requires multiple rocket launches, landings on and liftoffs from Mars. It’s a great way to test the technology and techniques before scaling the vehicles up to human size.

“Some of us have been talking about this for 10 to 12 years. Having discussions, planning, and trying to keep the momentum going to the point where suddenly it becomes a real program,” says Parker, “Now this is a real program. And Europe is right in the middle of it.”

Reader Q&A: What does lunar dust smell like?

Asked by: Philip Welply, St Albans

Apollo astronauts reported that lunar dust found inside their landers smelt like burnt gunpowder. Since there’s no chemical similarity between moondust and gunpowder, the smell could have been the dust reacting with oxygen and/or water inside the lander, or due to the release of charged particles from the Sun that had become trapped in the dust.

Curiously, though, lunar dust samples brought back to Earth from the Moon are odourless. So whatever caused the smell reported by the Apollo astronauts must have been temporary.

Read more: